While on a trip to Vancouver Island in British Columbia, we visited the quaint fishing village of Alert Bay, home to the First Nation people of the Kwakwaka’wakw. At the U’mista Cultural Centre we learned of the traditional potlatch ceremony, how it was misunderstood by missionaries and government agents. The practice was consequently outlawed, and those who continued the tradition were jailed.

While on a trip to Vancouver Island in British Columbia, we visited the quaint fishing village of Alert Bay, home to the First Nation people of the Kwakwaka’wakw. At the U’mista Cultural Centre we learned of the traditional potlatch ceremony, how it was misunderstood by missionaries and government agents. The practice was consequently outlawed, and those who continued the tradition were jailed.

The Potlatch“When one’s heart is glad, he gives away gifts. It was given to us by our Creator, to be our way of doing things, to be our way of rejoicing, we who are Indian. The potlatch was given to us to be our way of expressing joy” – Agnes Alfred, Alert Bay, 1980

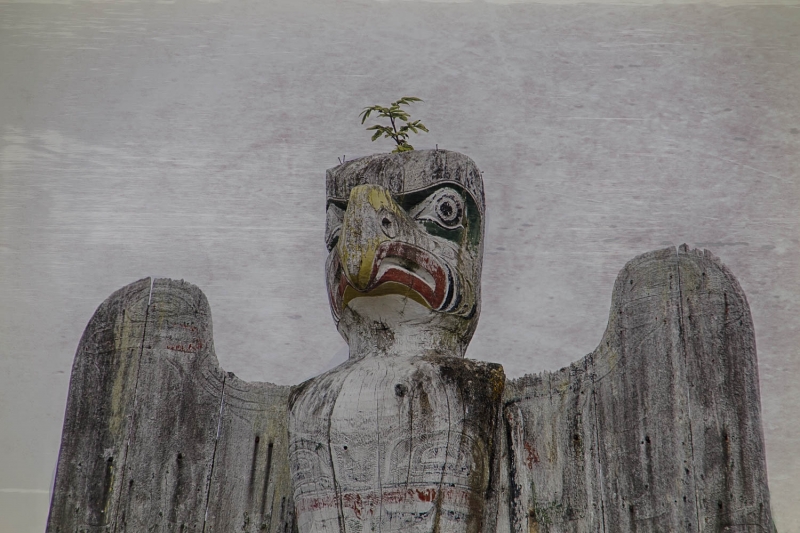

The potlatch ceremony marked important events in the lives of the Kwakwaka’wakw such as the naming of a child, a marriage, or mourning the dead. In addition to generous sharing of gifts, the ceremonies included dancing and the wearing of elaborate masks carved from cedar. The masks represented mythical eagles, bears, ravens and frogs, and were used in elaborate and theatrical dances that reflected the hosts’ genealogy and cultural wealth.

Missionaries who came to the island became increasingly frustrated over attempts to “civilize” the people, and in 1921 a law was passed to outlaw the potlatch ceremonies. Our Kwakwala guide told us that the common misunderstood belief was that canibalism was practiced at these gatherin gs. The Kwakwaka’wakw people were forced to give up their gift-giving ceremonies or be jailed. The ceremonial regalia, including the ornate carved cedar masks were confiscated; some went to private collections, some went Canadian museums. For years, the potlatch continued in secret, and “underground” ceremonies were held. Although the anti-potlatch law was deleted in 1951, those who had lost their treasures had not forgotten their loss. Efforts to repatriate these objects began, and many of them have been returned and are now on display at the U’mista Centre.

gs. The Kwakwaka’wakw people were forced to give up their gift-giving ceremonies or be jailed. The ceremonial regalia, including the ornate carved cedar masks were confiscated; some went to private collections, some went Canadian museums. For years, the potlatch continued in secret, and “underground” ceremonies were held. Although the anti-potlatch law was deleted in 1951, those who had lost their treasures had not forgotten their loss. Efforts to repatriate these objects began, and many of them have been returned and are now on display at the U’mista Centre.

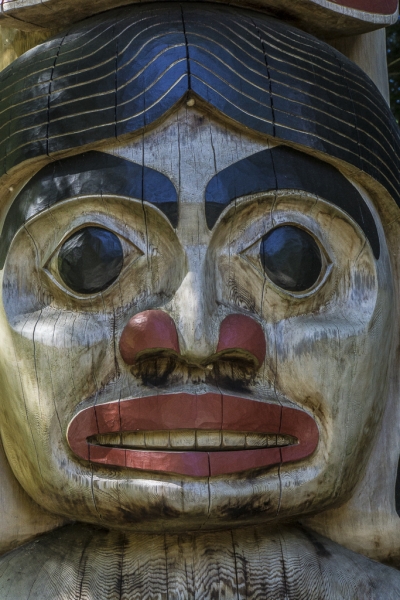

Dzunukwa, one of the mythological figures, is venerated as a bringer of wealth, but is also greatly feared by children, as an ogress who steals children and carries them home in her basket to eat. Her appearance is that of a naked, hairy, old monster with long pendulous breasts. In masks and totem pole images she is shown with bright red pursed lips because she is said to give off the call “Hu!” It is often told to children that the sound of the wind blowing through the cedar trees is actually the call of Dzunukwa.

Dzunukwa, one of the mythological figures, is venerated as a bringer of wealth, but is also greatly feared by children, as an ogress who steals children and carries them home in her basket to eat. Her appearance is that of a naked, hairy, old monster with long pendulous breasts. In masks and totem pole images she is shown with bright red pursed lips because she is said to give off the call “Hu!” It is often told to children that the sound of the wind blowing through the cedar trees is actually the call of Dzunukwa.

The meaning of U’mista In earlier days, people were sometimes taken captive by raiding parties. When they returned to their homes, either through payment of ransom or by retaliatory raid, they were said to have “u’mista”. the return of our treasures from distant museums is a form of u’mista. – U’mista Cultural Centre

Although photography was not allowed of the collection of U’mista Potlatch masks and artifacts, we did photograph many of the carved images on numerous totem poles that were similar to the carvings of the ornate potlatch masks. Symbolizing characters in mythology, some of these characters may appear as stylistic representations of objects in nature, while others are more realistically carved. Pole carvings may include animals, fish, plants, insects, and humans, or they may represent supernatural beings such as the Thunderbird. Some symbolize beings that can transform themselves into another form, appearing as combinations of animals or part-animal/part-human forms. These images are from the U’mista Centre lobby, the ‘Namgis Burial Grounds on Alert Bay, and some from the extensive totem pole collection at Capilano Suspension Bridge Park in Vancouver. More images from our trip to British Columbia, including whales and grizzlies can be seen here.